Probabilistic models for deep architectures¶

Of particular interest are Boltzmann machine models, certain variants of which are used in deep architectures such as Deep Belief Networks and Deep Boltzmann Machines. See section 5 of Learning Deep Architectures for AI.

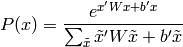

The Boltzmann distribution is generally defined on binary variables

, with

, with

where the denominator is simply a normalizing constant such that

, and the

, and the  indicates the nature

of the interaction (e.g. a positive value indicates that

indicates the nature

of the interaction (e.g. a positive value indicates that  et

et  prefer to take the same value) between pairs of

variables, and

prefer to take the same value) between pairs of

variables, and  indicates the inclination of a given

indicates the inclination of a given

to take a value of 1.

to take a value of 1.

Readings on probabilistic graphical models¶

See

Graphical models: probabilistic inference. M. I. Jordan and Y. Weiss. In M. Arbib (Ed.), The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks, 2nd edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

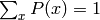

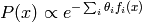

Certain distributions can be written  for

a vector of variables

for

a vector of variables  in the form

in the form

where  is the normalizing constant (called the partition function),

and the product is over cliques (subsets

is the normalizing constant (called the partition function),

and the product is over cliques (subsets  of elements of the vector

of elements of the vector  ),

and the

),

and the  are functions (one per clique) that indicate how

the variables in each clique interact.

are functions (one per clique) that indicate how

the variables in each clique interact.

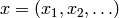

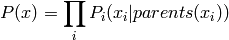

A particular case where  may be simplified a bit (factorized

over cliques) is the case of directed models where variables

are structured as a directed acyclic graph, with a topological ordering

that associates a group of parent variables

may be simplified a bit (factorized

over cliques) is the case of directed models where variables

are structured as a directed acyclic graph, with a topological ordering

that associates a group of parent variables  with

each variable

with

each variable  :

:

where it can be seen that there is one clique for a variable and its parents,

i.e.,  .

.

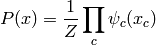

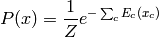

In the general case (represented with an undirected graph), the

potential functions  are directly parameterized,

often in the space of logarithms of

are directly parameterized,

often in the space of logarithms of  ,

leading to a formulation known as a Markov random field:

,

leading to a formulation known as a Markov random field:

where:math:E(x)=sum_c E_c(x_c) is called the energy function.

The energy function of a Boltzmann machine is a second degree polynomial

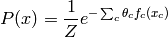

in  . The most common parameterization of Markov random fields

has the following form, which is log-linear:

. The most common parameterization of Markov random fields

has the following form, which is log-linear:

where the only free parameters are the  ,

and where the complete log likelihood (when

,

and where the complete log likelihood (when  is completely observed in each training example) is log-linear

in the parameters

is completely observed in each training example) is log-linear

in the parameters  . One can easily

show that this function is convex in

. One can easily

show that this function is convex in  .

.

Inference¶

One of the most important obstacles in the practical application of

the majority of probabilistic models is the difficulty of inference:

given certain variables (a subset of  ),

predict the marginal distribution (separately for each) or joint

distribution of certain other variables.

Let

),

predict the marginal distribution (separately for each) or joint

distribution of certain other variables.

Let  with

with  (hidden) being the variables

we would like to predict, and

(hidden) being the variables

we would like to predict, and  (visible)

being the observed subset.

One would like to calculate, or at least sample from,

(visible)

being the observed subset.

One would like to calculate, or at least sample from,

Inference is obviously useful if certain variables are missing, or if, while using the model, we wish to predict a certain variable (for example the class of an image) given some other variables (for example, the image itself). Note that if the model has hidden variables (variables that are never observed in the data) we do not try to predict the values directly, but we will still implicitly marginalize over these variables (sum over all configurations of these variables).

Inference is also an essential component of learning, in order to calculate gradients (as seen below in the case of Boltzmann machines) or in the use of the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm which requires a marginalization over all hidden variables.

In general, exact inference has a computational cost exponential in the size of the cliques of a graph (in fact, the unobserved part of the graph) because we must consider all possible combinations of values of the variables in each clique. See section 3.4 of Graphical models: probabilistic inference for a survey of exact inference methods.

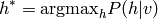

A simplifed form of inference consists of calculating not the entire distribution, but only the mode (the most likely configuration of values) of the distribution:

This is known as MAP = Maximum A Posteriori inference.

Approximate inference¶

The two principal families of methods for approximate inference in probabilistic models are Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods and variational inference.

The principle behind variational inference is the following. We will define a simpler model than the target model (the one that interests us), in which inference is easy, with a similar set of variables (though generally with more simple dependencies between variables than those contained in the target model). We then optimize the parameters of the simpler model so as to approximate the target model as closely as possible. Finally, we do inference using the simpler model. See section 4.2 of Graphical models: probabilistic inference for more details and a survey.

Inference with MCMC¶

In general  can be exponentially expensive to represent (in

terms of the number of hidden variables, because we must consider all possible

configurations of

can be exponentially expensive to represent (in

terms of the number of hidden variables, because we must consider all possible

configurations of  ). The principle behind Monte Carlo inference is

that we can approximate the distribution

). The principle behind Monte Carlo inference is

that we can approximate the distribution  using samples from

this distribution. Indeed, in practice we only need an expectation (for

example, the expectation of the gradient) under this conditional distribution.

We can thus approximate the desired expectation with an average of these

samples.

using samples from

this distribution. Indeed, in practice we only need an expectation (for

example, the expectation of the gradient) under this conditional distribution.

We can thus approximate the desired expectation with an average of these

samples.

See the page site du zéro sur Monte-Carlo (in French) for a gentle introduction.

Unfortunately, for most probabilistic models, even sampling from  exactly is not feasible (taking time exponential in the dimension of de

exactly is not feasible (taking time exponential in the dimension of de

). Therefore the most general approach is based on an approximation

of Monte-Carlo sampling called Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC).

). Therefore the most general approach is based on an approximation

of Monte-Carlo sampling called Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC).

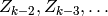

A (first order) Markov chain is a sequence of random variables

, where

, where  is independent of

is independent of

given

given  :

:

The goal of MCMC is to construct a Markov chain whose asymptotic

marginal distribution, i.e. the distribution of  as

as

, converges towards a given target

distribution, such as

, converges towards a given target

distribution, such as  or

or  .

.

Gibbs sampling¶

Numerous MCMC-based sampling methods exist. The one most commonly used for deep architectures is Gibbs sampling. It is simple and has a certain plausible analogy with the functioning of the brain, where each neuron decides to send signals with a certain probability as a function of the signals it receives from other neurons.

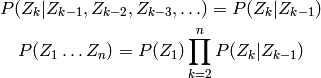

Let us suppose that we wish to sample from the distribution  where

where  is a set of variables

is a set of variables  (we could optionally

have a set of variables upon which we have conditioned, but this would

not change the procedure, so we ignore them in the following description).

(we could optionally

have a set of variables upon which we have conditioned, but this would

not change the procedure, so we ignore them in the following description).

Let  , i.e.

all variables in

, i.e.

all variables in  excluding

excluding  . Gibbs sampling is

performed using the following algorithm:

. Gibbs sampling is

performed using the following algorithm:

- Choose an initial value of

in an arbitrary manner (random or not)

in an arbitrary manner (random or not) - For each step of the Markov chain:

- Iterate over each

in

in

- Draw

from the conditional distribution

from the conditional distribution

- Draw

- Iterate over each

In some cases one can group variables in  into blocks or groups of

variables such that drawing samples for an entire group, given the others, is

easy. In this case it is advantageous to interpret the algorithm above with

into blocks or groups of

variables such that drawing samples for an entire group, given the others, is

easy. In this case it is advantageous to interpret the algorithm above with

as the

as the  group rather than the

group rather than the

variable. This is known as block Gibbs sampling.

variable. This is known as block Gibbs sampling.

The gradient in a log-linear Markov random field¶

See Learning Deep Architectures for AI for detailed derivations.

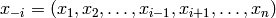

Log-linear Markov random fields are undirected probabilistic models where

the energy function is linear in the parameters  of the model:

of the model:

where  are known as sufficient statistics

of the model, because the expectations

are known as sufficient statistics

of the model, because the expectations ![E[f_i(x)]](_images/math/3eba7a57afb4739b629719623a47a16ec9472f85.png) are

sufficient for characterizing the distribution and estimating parameters.

are

sufficient for characterizing the distribution and estimating parameters.

Note that  is associated with

each clique in the model (in general, only a sub-vector of

is associated with

each clique in the model (in general, only a sub-vector of  influences each

influences each  ).

).

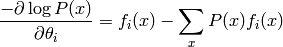

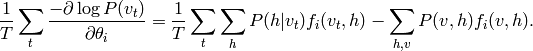

Getting back to sufficient statistics, one can show that the gradient of the log likelihood is as follows:

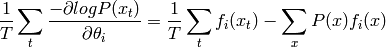

and the average gradient over training examples  is thus

is thus

Thus, it is clear that the gradient vanishes when the average of the sufficient statistics under the training distribution equals their expectation under the model distribution :math:`P`.

Unfortunately, calculating this gradient is difficult. We do not want

to sum over all possible  , but fortunately one can obtain

a Monte-Carlo approximation by one or more samples from

, but fortunately one can obtain

a Monte-Carlo approximation by one or more samples from  ,

which gives us a noisy estimate of the gradient. In general, however,

even to obtain an unbiased sample from

,

which gives us a noisy estimate of the gradient. In general, however,

even to obtain an unbiased sample from  is exponentially

costly, and thus one must use an MCMC method.

is exponentially

costly, and thus one must use an MCMC method.

We refer to the terms of the gradient due to the numerator of

the probability density ( ) as the ‘positive phase’

gradient, and the terms of the gradient corresponding to the partition

function (denominator of the probability density) as the

‘negative phase’ gradient.

) as the ‘positive phase’

gradient, and the terms of the gradient corresponding to the partition

function (denominator of the probability density) as the

‘negative phase’ gradient.

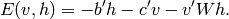

The Boltzmann Machine¶

A Boltzmann machine is an undirected probabilistic model, a particular

form of log-linear Markov random field, containing both visible and hidden

variables, where the energy function is a second degree polynomial of

the variables  :

:

The classic Boltzmann machine has binary variables and

inference is conducted via Gibbs sampling, which requires samples

from  . It can be easily shown that

. It can be easily shown that

where  is the

is the  row of

row of  excluding

the

excluding

the  element (the diagonal of

element (the diagonal of  is 0 in this model). Thus, we see the link with networks of neurons.

is 0 in this model). Thus, we see the link with networks of neurons.

Restricted Boltzmann Machines¶

A Restricted Boltzmann Machine, or RBM, is a Boltzmann machine without

lateral connections between the visible units  or between

the hidden units

or between

the hidden units  . The energy function thus becomes

. The energy function thus becomes

where the matrix  is entirely 0 except in the submatrix

is entirely 0 except in the submatrix  .

The advantage of this connectivity restriction is that inferring

.

The advantage of this connectivity restriction is that inferring

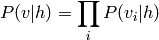

(and also

(and also  ) becomes very easy, can be performed

analytically, and the distribution factorizes:

) becomes very easy, can be performed

analytically, and the distribution factorizes:

and

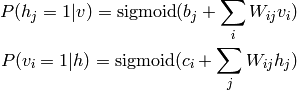

In the case where the variables (“units”) are binary, we obtain once again have a sigmoid activation probability:

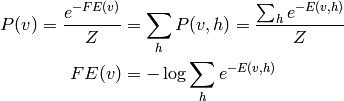

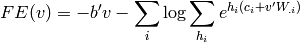

Another advantage of the RBM is that the distribution  can

be calculated analytically up to a constant (the unknown constant

being the partition function). This permits us to define a generalization

of the notion of an energy function in the case when we wish to marginalize

over the hidden variables: the free energy (inspired by notions from

physics)

can

be calculated analytically up to a constant (the unknown constant

being the partition function). This permits us to define a generalization

of the notion of an energy function in the case when we wish to marginalize

over the hidden variables: the free energy (inspired by notions from

physics)

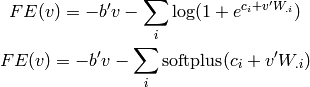

and in the case of RBMs, we have

where the sum over  is a sum over values that the hidden variables

can take, which in the case of binary units yields

is a sum over values that the hidden variables

can take, which in the case of binary units yields

Gibbs sampling in RBMs¶

Although sampling from  is easy and immediate in an RBM,

drawing samples from

is easy and immediate in an RBM,

drawing samples from  or from

or from  cannot be done

exactly and is thus generally accomplished with MCMC, most commonly with

block Gibbs sampling, where we take advantage of the fact that

sampling from

cannot be done

exactly and is thus generally accomplished with MCMC, most commonly with

block Gibbs sampling, where we take advantage of the fact that

sampling from  and

and  is easy:

is easy:

In order to visualize the generated data at step  , it is better

to use expectations (i.e.

, it is better

to use expectations (i.e. ![E[v^{(k)}_i|h^{(k-1)}]=P(v^{(k)}_i=1|h^{(k-1)})](_images/math/0b24c887f18bba73dd78997bd6147e82133bf11d.png) )

which are less noisy than the samples

)

which are less noisy than the samples  themselves.

themselves.

Training RBMs¶

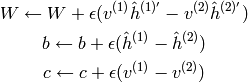

The exact gradient of the parameters of an RBM (for an example  ) is

) is

![\frac{\partial \log P(v)}{\partial W} = v' E[h | v] - E[v' h]

\frac{\partial \log P(v)}{\partial b} = E[h | v] - E[h]

\frac{\partial \log P(v)}{\partial c} = v - E[v]](_images/math/9a8b762b1757265330bbcbd4863f3fe25c2680d5.png)

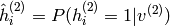

where the expectations are under the distribution of the RBM. The conditional

expectations can be calculated analytically (since ![E[h_i | v]=P(h_i=1|v)=](_images/math/b761f88916c58b56ce8cc558c7872804f8534f4b.png) the output of a hidden unit, for binary

the output of a hidden unit, for binary  )

but the unconditional expectations must be approximated using MCMC.

)

but the unconditional expectations must be approximated using MCMC.

Contrastive Divergence¶

The first and simplest approximation of ![E[v' h]](_images/math/d13085f3fcc28c68acc7c2e0d58afb6f41b35f87.png) , i.e., for

obtaining ‘negative examples’ (for the ‘negative phase’ gradient),

consists of running a short Gibbs chain (of

, i.e., for

obtaining ‘negative examples’ (for the ‘negative phase’ gradient),

consists of running a short Gibbs chain (of  steps) beginning at

a training example. This algorithm is known as CD-k

(Contrastive Divergence with k steps). See algorithm 1

in Learning Deep Architectures for AI:

steps) beginning at

a training example. This algorithm is known as CD-k

(Contrastive Divergence with k steps). See algorithm 1

in Learning Deep Architectures for AI:

where  is the gradient step size, and we refer to the

notation for Gibbs sampling from RBMs above, with

is the gradient step size, and we refer to the

notation for Gibbs sampling from RBMs above, with

denotes the vector of probabilities

denotes the vector of probabilities  and in the same fashion

and in the same fashion  .

.

What is surprising is that even with  , we obtain

RBMs that work well in the sense that they extract good features

from the data (which we can verify visually byt looking at the filters,

the stochastic reconstructions after one step of Gibbs, or quantitatively

by initializing each layer of a deep network with

, we obtain

RBMs that work well in the sense that they extract good features

from the data (which we can verify visually byt looking at the filters,

the stochastic reconstructions after one step of Gibbs, or quantitatively

by initializing each layer of a deep network with  and

and

obtained by pretraining an RBM at each layer).

obtained by pretraining an RBM at each layer).

It can be shown that CD-1 is very close to the training procedure of an autoencoder by minimizing reconstruction error, and one can see that the reconstruction error diminishes in a mostly monotonic fashion during CD-1 training.

It can also be shown that CD-k tends to the true gradient (in expected value) when k becomes large, but at the same time increases computation time by a factor of k.

Persistent Contrastive Divergence¶

In order to obtain a less biased estimator of the true gradient without

significantly increasing the necessary computation time, we can use the

Persistent Contrastive Divergence (PCD) algorithm. Rather than restarting

a Gibbs chain after each presentation of a training example  ,

PCD keeps a chain running in order to obtain negative examples. This chain

is a bit peculiar because its transition probabilities change (slowly) as

we update the parameters of the RBM. Let

,

PCD keeps a chain running in order to obtain negative examples. This chain

is a bit peculiar because its transition probabilities change (slowly) as

we update the parameters of the RBM. Let  be the state

of our negative phase chain. The learning algorithm is then

be the state

of our negative phase chain. The learning algorithm is then

Experimentally we find that PCD is better in terms of generating examples

that resemble the training data (and in terms of the likelihood

) than CD-k, and is less sensitive to the initialization

of the Gibbs chain.

) than CD-k, and is less sensitive to the initialization

of the Gibbs chain.

Stacked RBMs and DBNs¶

RBMs can be used, like autoencoders, to pretrain a deep neural network in an

unsupervised manner, and finish training in the usual supervised fashion.

One stacks RBMs with the hidden layer of one (given its input) i.e., les

or

or  , becomes the data for the next

layer.

, becomes the data for the next

layer.

The pseudocode for greedy layer-by-layer training of a stack of RBMs

is presented in section 6.1 (algorithm 2) of Learning Deep Architectures

for AI. To train the  RBM, we propagate forward

samples

RBM, we propagate forward

samples  or the posteriors

or the posteriors  through

the

through

the  previously trained RBMs and use them as data for training

the

previously trained RBMs and use them as data for training

the  RBM. They are trained one at a time: once

we stop training the

RBM. They are trained one at a time: once

we stop training the  , we move on to the

, we move on to the

.

.

An RBM has the same parameterization as a layer in a classic neural network

(with logistic sigmoid hidden units), with the difference that we use

only the weights  and the biases

and the biases  of the hidden units

(since we only need

of the hidden units

(since we only need  and not

and not  ).

).

Deep Belief Networks¶

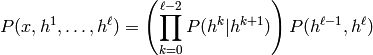

We can also consider a stacking of RBMs in a generative manner, and we call these models Deep Belief Networks:

where we denote  and

and  as the random variable (vector)

associated with layer

as the random variable (vector)

associated with layer  . The last two layers have a joint distribution

given by an RBM (the last of the stack). The RBMs below serve

only to define the conditional probabilities

. The last two layers have a joint distribution

given by an RBM (the last of the stack). The RBMs below serve

only to define the conditional probabilities  of the DBN, where

of the DBN, where  play the role of visible units and

:math:`h^{k+1}`similarly play the role of hidden units in RBM k+1.

play the role of visible units and

:math:`h^{k+1}`similarly play the role of hidden units in RBM k+1.

Sampling from a DBN is thus performed as follows:

Sample a

from the top RBM (number

), for example by running a Gibbs chain

- For k from

to 1

- sample the visible units (

) given the hidden units (

) in RBM k

Return

, the last sample obtained, which is the result of generating from the DBN

Unfolding an RBM and RBM - DBN equivalence¶

It can be shown (see section 8.1 of

Learning Deep Architectures for AI.)

that an RBM corresponds to DBN with a particular architecture, where the

weights are shared between all the layers:

level 1 of the DBN uses the weights  of the RBM,

level 2 uses the weights

of the RBM,

level 2 uses the weights  , level 3 uses

, level 3 uses  , etc. alternating

between

, etc. alternating

between  and

and  . The last pair of layers of the DBN is an RBM with weights

. The last pair of layers of the DBN is an RBM with weights  or :math`W’` depending on whether the number of layers

is odd or even.

Note that in this equivalence, the DBN has layer sizes that alternate

(number of visible units of the RBM, number of hidden units of the RBM,

number of visibles, etc.)

or :math`W’` depending on whether the number of layers

is odd or even.

Note that in this equivalence, the DBN has layer sizes that alternate

(number of visible units of the RBM, number of hidden units of the RBM,

number of visibles, etc.)

In fact we can continue the unfolding of an RBM infinitely and obtain an infinite directed network with shared weights, equivalently. See figure 13 in the same section, 8.1.

It can be seen that this infinite network corresponds exactly to an infinite

Gibbs chain that leads to (finishes on) the visible layer of the original

RBM, i.e. that generates the same examples. The even layers correspond to

sampling  (of the original RBM) and the odd layers to

sampling

(of the original RBM) and the odd layers to

sampling  .

.

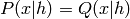

Finally, it can be shown that if we take an RBM and unfold it one time

(mirrored), the continued training of the new RBM on top (initialized

with  ) maximizes a lower bound on the log likelihood of the

corresponding DBN. In passing from an RBM to a DBN, we replace the marginal

distribution

) maximizes a lower bound on the log likelihood of the

corresponding DBN. In passing from an RBM to a DBN, we replace the marginal

distribution  of the RBM (which is encoded implicitly in

the parameters of the RBM) with the distribution generated by the part of

the DBN above this RBM (the DBN consists of all layers above

of the RBM (which is encoded implicitly in

the parameters of the RBM) with the distribution generated by the part of

the DBN above this RBM (the DBN consists of all layers above  ),

since this

),

since this  corresponds to visible units of this DBN. The proof

is simple and instructive, and uses the letter Q for the probabilities

according to the RBM (at the bottom) and the letter P for the probabilities

according to the DBN obtained by modeling

corresponds to visible units of this DBN. The proof

is simple and instructive, and uses the letter Q for the probabilities

according to the RBM (at the bottom) and the letter P for the probabilities

according to the DBN obtained by modeling  differently (i.e.

by replacing

differently (i.e.

by replacing  by

by  ). We also remark that

). We also remark that

, but this is not true for

, but this is not true for  and

and

.

.

This shows that one can actually increase the lower bound (last line) by

doing maximum likelihood training of  using as training data the

using as training data the

drawn from

drawn from  , where

, where  is drawn from the

training distribution of the bottom RBM. Since we have decoupled the weights

below from those above, we don’t touch the bottom RBM (

is drawn from the

training distribution of the bottom RBM. Since we have decoupled the weights

below from those above, we don’t touch the bottom RBM ( and

and

), and only modify

), and only modify  .

.

Approximate inference in DBNs¶

Contrary to the RBM, inference in DBNs (inferring the states of the hidden

units given the visible units) is very difficult. Given that we

initialize DBNs as a stack of RBMs, in practice the following approximation

is used: sample the  given the

given the  using the new

weights of level

using the new

weights of level  . This would be exact inference if this was

still an isolated RBM, but it is no longer exact with the DBN.

. This would be exact inference if this was

still an isolated RBM, but it is no longer exact with the DBN.

We saw that this is an approximation in the previous section because the

marginal  (of the DBN) differs from the marginal

(of the DBN) differs from the marginal  (of the bottom RBM), after modifying the upper weights so that they are

no longer the tranpose of the bottom weights, and thus

(of the bottom RBM), after modifying the upper weights so that they are

no longer the tranpose of the bottom weights, and thus  differs from

differs from  .

.

Deep Boltzmann Machines¶

Finally, we can also use a stack of RBMs for initializing a deep Boltzmann machine (Salakhutdinov and Hinton, AISTATS 2009). This is a Boltzmann machine organized in layers, where each layer is connected the layer below and the layer above, and there are no within-layer connections.

Note that the weights are somehow two times too big when doing the initialization described above, since now each unit receives input from the layer above and the layer below, whereas in the original RBM it was either one or the other. Salakhutdinov proposes thus dividing the weights by two when we make the transition from stacking RBMs to deep Boltzmann machines.

It is also interesting to note that according to Salakhutdinov, it is crucial to initialize deep Boltzmann machines as a stack of RBMs, rather than with random weights. This suggests that the difficulty of training deep deterministic MLP networks is not unique to MLPs, and that a similar difficulty is found in deep Boltzmann machines. In both cases, the initialization of each layer according to a local training procedure seems to help a great deal. Salakhutdinov obtains better results with his deep Boltzmann machine than with an equivalent-sized DBN, although training the deep Boltzmann machine takes longer.

. The average gradient

of the negative log likelihood of the observed data is thus

. The average gradient

of the negative log likelihood of the observed data is thus

.

.