Introduction to Gradient-Based Learning¶

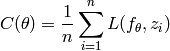

Consider a cost function  which maps a parameter vector

which maps a parameter vector  to a scalar

to a scalar  which we would like to minimize. In machine

learning the cost function is typically the average or the expectation of

a loss functional:

which we would like to minimize. In machine

learning the cost function is typically the average or the expectation of

a loss functional:

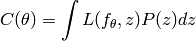

(this is called the training loss) or

(this is called the generalization loss), where in supervised

learning we have  and

and  is a prediction of

is a prediction of  , indexed by the parameters

, indexed by the parameters  .

.

The Gradient¶

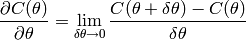

The gradient of the function  of a single scalar

of a single scalar  is formally defined as follows:

is formally defined as follows:

Hence it is the variation  induced by a change

induced by a change  ,

when

,

when  is very small.

is very small.

When  is a vector, the gradient

is a vector, the gradient  is a vector with one element

is a vector with one element  per

per  , where we consider the other

parameters fixed, we only make the change

, where we consider the other

parameters fixed, we only make the change  and we measure

the resulting

and we measure

the resulting  . When

. When  is small then

is small then

becomes

becomes  .

.

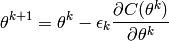

Gradient Descent¶

We want to find a  that minimizes

that minimizes  .

If we are able to solve

.

If we are able to solve

then we can find the minima (and maxima and saddle points), but in general

we are not able to find the solutions of this equation, so we use numerical

optimization methods. Most of these are based on the idea of local descent:

iteratively modify  so as to decrease

so as to decrease  , until

we cannot anymore, i.e., we have arrived at a local minimum (maybe global

if we are lucky).

, until

we cannot anymore, i.e., we have arrived at a local minimum (maybe global

if we are lucky).

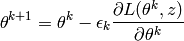

The simplest of all these gradient-based optimization techniques is gradient descent. There are many variants of gradient descent, so we define here ordinary gradient descent:

where  represents our parameters at iteration

represents our parameters at iteration  and

and  is a scalar that is called the learning rate, which

can either be chosen fixed, adaptive or according to a fixed decreasing schedule.

is a scalar that is called the learning rate, which

can either be chosen fixed, adaptive or according to a fixed decreasing schedule.

Stochastic Gradient Descent¶

We exploit the fact that  is an average, generally over i.i.d.

(independently and identically distributed) examples, to make updates to

is an average, generally over i.i.d.

(independently and identically distributed) examples, to make updates to  much more often, in the extreme (and most common) case after each example:

much more often, in the extreme (and most common) case after each example:

where  is the next example from the training set, or the next example

sampled from the training distribution, in the online setting (where we have not

a fixed-size training set but instead access to a stream of examples from

the data generating process). Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is a more

general principle in which the update direction is a random variable

whose expectations is the true gradient of interest. The convergence

conditions of SGD are similar to those for gradient descent, in spite

of the added randomness.

is the next example from the training set, or the next example

sampled from the training distribution, in the online setting (where we have not

a fixed-size training set but instead access to a stream of examples from

the data generating process). Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is a more

general principle in which the update direction is a random variable

whose expectations is the true gradient of interest. The convergence

conditions of SGD are similar to those for gradient descent, in spite

of the added randomness.

SGD can be much faster than ordinary (also called batch) gradient descent, because it makes updates much more often. This is especially true for large datasets, or in the online setting. In fact, in machine learning tasks, one only uses ordinary gradient descent instead of SGD when the function to minimize cannot be decomposed as above (as a mean).

Minibatch Stochastic Gradient Descent¶

This is a minor variation on SGD in which we obtain the update direction by

taking the average over a small batch (minibatch) of  examples (e.g. 10, 20 or 100).

The main advantage is that instead of doing

examples (e.g. 10, 20 or 100).

The main advantage is that instead of doing  Vector x Matrix products

one can often do a Matrix x Matrix product where the first matrix has

Vector x Matrix products

one can often do a Matrix x Matrix product where the first matrix has  rows,

and the latter can be implemented more efficiently (sometimes 2 to 10 times faster,

depending on the sizes of the matrices).

rows,

and the latter can be implemented more efficiently (sometimes 2 to 10 times faster,

depending on the sizes of the matrices).

Minibatch SGD has the advantage that it works with a slightly less noisy

estimate of the gradient (more so as  increases). However, as

the minibatch size increases, the number of updates done per computation

done decreases (eventually it becomes very inefficient, like batch gradient

descent). There is an optimal trade-off (in terms of computational efficiency)

that may vary depending on the data distribution and the particulars of

the class of function considered, as well as how computations are implemented

(e.g. parallelism can make a difference).

increases). However, as

the minibatch size increases, the number of updates done per computation

done decreases (eventually it becomes very inefficient, like batch gradient

descent). There is an optimal trade-off (in terms of computational efficiency)

that may vary depending on the data distribution and the particulars of

the class of function considered, as well as how computations are implemented

(e.g. parallelism can make a difference).

Momentum¶

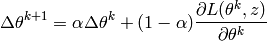

Another variation that is similar in spirit to minibatch SGD is the use of so-called momentum: the idea is to compute on-the-fly (online) a moving average of the past gradients, and use this moving average instead of the current example’s gradient, in the update equation. The moving average is typically an exponentially decaying moving average, i.e.,

where  is a hyper-parameter that controls the how much

weight is given in this average to older vs most recent gradients.

is a hyper-parameter that controls the how much

weight is given in this average to older vs most recent gradients.

Choosing the Learning Rate Schedule¶

If the step size is too large – larger than twice the largest eigenvalue of the

second derivative matrix (Hessian) of  –, then gradient steps will go upward

instead of downward. If the step size is too small, then convergence is slower.

–, then gradient steps will go upward

instead of downward. If the step size is too small, then convergence is slower.

The most common choices of learning rate schedule ( ) are the following:

) are the following:

constant schedule,

: this is the most common choice.

It in theory gives an exponentially larger

weight to recent examples, and is particularly appropriate in a non-stationary

environment, where the distribution may change. It is very robust but

error will stop improving after a while, where a smaller learning rate could

yield a more precise solution (approaching the minimum a bit more).

: this is the most common choice.

It in theory gives an exponentially larger

weight to recent examples, and is particularly appropriate in a non-stationary

environment, where the distribution may change. It is very robust but

error will stop improving after a while, where a smaller learning rate could

yield a more precise solution (approaching the minimum a bit more). schedule:

schedule:  .

.This schedule is guaranteed to reach asymptotic convergence (as

)

because it satisfies the following requirements:

)

because it satisfies the following requirements:

and this is true for any

but

but  must be small enough

(to avoid divergence, where the error rises instead of decreasing

must be small enough

(to avoid divergence, where the error rises instead of decreasingA disadvantage is that an additional hyper-parameter

is introduced.

Another is that in spite of its guarantees, a poor choice of

is introduced.

Another is that in spite of its guarantees, a poor choice of  can

yield very slow convergence.

can

yield very slow convergence.

Flow Graphs, Chain Rule and Backpropagation: Efficient Computation of the Gradient¶

Consider a function (in our case it is  ) of several arguments,

and we wish to compute it as well as its derivative (gradient) w.r.t. some of its

arguments. We will decompose the computation of the function in terms of

elementary computations for which partial derivatives are easy to compute,

forming a flow graph (as already discussed there).

A flow graph is an acyclic graph where each node represents the result

of a computation that is performed using the values associated with

connected nodes of the graph. It has input nodes (with no predecessors)

and output nodes (with no successors).

) of several arguments,

and we wish to compute it as well as its derivative (gradient) w.r.t. some of its

arguments. We will decompose the computation of the function in terms of

elementary computations for which partial derivatives are easy to compute,

forming a flow graph (as already discussed there).

A flow graph is an acyclic graph where each node represents the result

of a computation that is performed using the values associated with

connected nodes of the graph. It has input nodes (with no predecessors)

and output nodes (with no successors).

Each node of the flow graph is associated with a symbolic expression

that defines how its value is computed in terms of the values of its children

(the nodes from which it takes its input). We will focus on flow graphs

for the purpose of efficiently computing gradients, so we will keep track

of gradients with respect to a special output node (denoted  here to refer to a loss to be differentiated with respect to parameters,

in our case). We will associate with each node

here to refer to a loss to be differentiated with respect to parameters,

in our case). We will associate with each node

- the node value

- the symbolic expression that specifies how to compute the node value in terms of the value of its predecessors (children)

- the partial derivative of

with respect to the node value

- the symbolic expressions that specify to how compute the partial derivative of each node value with respect to the values of its predecessors.

Let  be the output scalar node of the flow graph, and consider

an arbitrary node

be the output scalar node of the flow graph, and consider

an arbitrary node  whose parents (those nodes

whose parents (those nodes  taking the value

computed at

taking the value

computed at  as input).

In addition to the value

as input).

In addition to the value  (abuse of notation) associated

with node

(abuse of notation) associated

with node  , we will also associate with each node

, we will also associate with each node  a partial derivative

a partial derivative  .

.

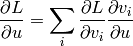

The chain rule for derivatives specifies how the partial

derivative  for a node

for a node  can be obtained recursively from the partial derivatives

can be obtained recursively from the partial derivatives  for its parents

for its parents  :

:

Note that  which starts the recursion at the

root node of the graph (node that in general it is a graph, not a tree, because there

may be multiple paths from a given node to the root – output – node).

Note also that each

which starts the recursion at the

root node of the graph (node that in general it is a graph, not a tree, because there

may be multiple paths from a given node to the root – output – node).

Note also that each  is an expression (and a corresponding

value, when the inputs are given) that is associated with an arc of the graph

(and each arc is associated with one such partial derivative).

is an expression (and a corresponding

value, when the inputs are given) that is associated with an arc of the graph

(and each arc is associated with one such partial derivative).

Note how the gradient computations involved in this recipe go exactly in the

opposite direction compared to those required to compute  .

In fact we say that gradients are back-propagated, following the

arcs backwards. The instantiation of this procedure for computing

gradients in the case of feedforward multi-layer neural networks

is called the **back-propagation algorithm**.

.

In fact we say that gradients are back-propagated, following the

arcs backwards. The instantiation of this procedure for computing

gradients in the case of feedforward multi-layer neural networks

is called the **back-propagation algorithm**.

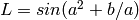

In the example already shown earlier,

and there are two paths from

and there are two paths from  to

to  .

.

This recipe gives us the following nice guarantee. If the computation of  is expressed with

is expressed with  computations expressed through

computations expressed through  nodes

(and each node computation requires a constant computation time)

and

nodes

(and each node computation requires a constant computation time)

and  arcs, then

computing all the partial derivatives

arcs, then

computing all the partial derivatives  requires (at most)

requires (at most)  computations, using the above recursion

(in general, with a bounded in-degree, this is also

computations, using the above recursion

(in general, with a bounded in-degree, this is also  ).

Furthermore, this is a lower bound, i.e., it is not possible to

compute the gradients faster (up to an additive and multiplicative constant).

).

Furthermore, this is a lower bound, i.e., it is not possible to

compute the gradients faster (up to an additive and multiplicative constant).

Note that there are many ways in which to compute these gradients, and

whereas the above algorithm is the fastest one, it is easy to write

down an apparently simple recursion that would instead be exponentially

slower, e.g., in  . In general

. In general

can be written as

a sum over all paths in the graph from

can be written as

a sum over all paths in the graph from  to

to  of the products of the partial derivatives along each path.

of the products of the partial derivatives along each path.

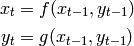

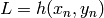

An illustration of this is with a graph with the following structure:

where there are  such

such  pairs of node, ending with

pairs of node, ending with

and with input nodes

and with input nodes  and

and  .

The number of paths from

.

The number of paths from  to

to  is

is  .

Note by mental construction how the number of paths doubles as we

increase

.

Note by mental construction how the number of paths doubles as we

increase  by 1.

by 1.